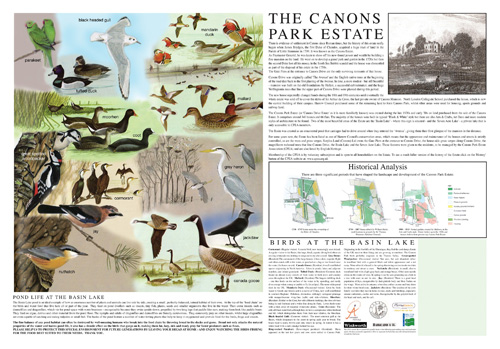

“We’re not all smelly vampires and thanks for the boxes on the trees round Basin Lake”

Pipistrelle who asked to remain anonymous

A few years ago I was staying on an island in the Maldives. Huge bright-red noisy fruit (eating) bats were everywhere.

UK bats are, of course, far more discreet. After all, they are English. Our bats have conservative darker fur, they only squeak when squoken to and on the size scale, they are at the tiny end of small.

The Pipistrelle: The bat (left and right) is the commonest of our 17 UK species, the pipistrelle. It weighs about 5g (less than a 2p coin) and woefully underperforms if it wants to preserve the fearful vampire image. That tiny creature only eats insects –about 3,000 a night.

|

|

The Brown Long-Eared Bat: These are almost as common as the pipistrelle. This bats ears are so large it could have royal connections.

|

|

Bat Decline: Despite this display of quiet good manners, our bat population has been on the decline for the last 100 years.

If, like bats, your diet is so specialised, the reduction of insect prey leaves your larder as bare as Old Mother Hubbard’s cupboard.

In this instance the cupboard has shrunk due to loss of wooded roost sites, wetlands and hedgerows. The use of farm and gardening insecticides along with the increase of high intensity farming have not helped.

Even when bats move into buildings as their habitats shrink and disappear, they find new threats to their wellbeing - toxic timber treatment chemicals.

Their rather restrained British breeding habits don’t help.

Bats usually have one baby at a time. Like humans, they are born live and feed on their mother’s milk. They do not reach maturity until they are two years old and live up to 30 years.

Basin lake bat housing development: Luckily, an overgrown area at the back right corner round the basin lake, viewed from the road, has all the things bats need and love. If bats went on Location, Location, Location they would all ask Kirstie and Phil for trees and cover every time. Trees are to bats what Monaco apartments are to millionaires; though I suspect that there is less guano in a Monaco apartment.

Most bats roost in trees. Trees give them shelter and attract a wide diversity of those irresistible insects.

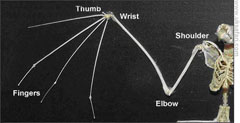

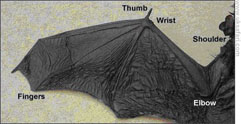

Being the only mammal that truly flies has its downside. Unfortunately, because their hands have evolved into wings, bats are useless at DIY.

|

|

They can’t bore holes in the trees or make nests so they are prepared to pay the premium and find something already done up by other animals, the result of natural wood decay or a conveniently sited bat box and just move in.

Bats live in the higher canopy during the summer when they want somewhere warm to give birth and suckle their young and hibernate lower and deeper during the winter.

The surrounding woodlands and the lake provide a great foraging habitat and there is more...

Bats like to travel safely between their roost and their supper. They can see as well as we can but this is not as useful as it could be for an animal that hunts at night.

Boats hunting submarines use sonar, bats use echolocation. They like lots of objects available to echo back their calls so they can navigate. This cover also protects them from their predators far better than open spaces.

So bat boxes are what is what is planned for the wilderness area round the Basin Lake, for bats, it’s an ideal location. It is a joint venture with the Woodland Trust so that the area can be better managed and threatened wildlife encouraged.

Some myths exposed: Bats are ideal neighbours, their navigation skills are so good they won’t get caught in your hair.

Human contact with bats is exceptionally rare. Passive surveys since 1986 found few with any live viruses. The only chance of catching any disease from bats is by handling them. If you have seen bats darting about, you will realise how unlikely that would be.

Wood is good

If you potter round the lakes and notice a certain degree of untidiness, rotting trees and the like, it’s not a sign of poor house-keeping, you are just observing good nature conservation; a welcome sight for a globally threatened species like a Stag Beetle.

Stag beetles are Britain’s largest insect and because they are so easy to recognise, they are one of the best known.

The male’s huge jaws resemble a stag’s antlers and are difficult to miss. Fierce looking but useless for biting, they use these appendages to fight other males. Like stags, these fights are usually just displays of aggression. As soon as one realises the other is going to win, the loser looks nonchalant to hide his embarrassment, pretends he does not care and makes a strategic withdrawal.

Lady beetles have less impressive mouth parts but have been known to administer a nasty nip so I expect the males are careful to have a good excuse if they are late home in the evening.

Once so common, this magnificent beast is now rare in Britain because their favourite habitats, woodlands, are becoming scarce. This poses them with a considerable dilemma as all stages of the Stag Beetle’s life-cycle depend on dead wood.

From egg to adult: When Stag Beetle eggs hatch, a cream coloured larva emerges. It is fat and wrinkly with six stubby legs. It also has the trademark prominent, tough jaws, perfect for that well known stag beetle delicacy, decaying wood.

Larvae eat rotting wood and roots. After chewing wet sawdust for years, it becomes a pupa (left) which stays hidden in the decaying tree trunk. Here it develops slowly throughout the winter until a fully formed adult emerges when the weather becomes warmer in May or June.

Whilst the larva lives for 3-5 years, the fully grown adult lasts for four months (from May to August). I suppose the burden of responsibility that comes with adulthood takes years off their lives. It certainly affects their appetite. They might dine on tree sap or eat nothing at all, entomologists aren’t sure yet.

The male is rather large and clumsy. A beetle whose flight path can be very erratic, bumps into things and crash-lands is not a great candidate for the insect Red Arrows. How odd that they choose to fly at dusk to find a mate.

The successful beetles find a female and after mating, she finds some moist decayed wood to lay her eggs and then dies. The male dies soon after; Shakespeare’s “Romeo & Juliet” in miniature.

The beetle plan: To help increase their numbers, in partnership with the Woodland Trust, that same back right corner round the Basin Lake is going to be converted into stag beetle heaven by leaving a proportion of dead or dying timber to rot down naturally. This will offset some of the habitat reduction caused by tidying woodlands, parks and gardens, the burning or chipping of dead wood and the stump-grinding of felled trees. The beetles will still have to contend with the urban threats, traffic, feet, cats, birds, foxes and some might help feed the bats. Some might find this ironic.

Article by Peter Bennett